Brazil: Boom, Bust, Bolsonaro and Beyond

- Nov 8, 2022

- Anand Sheth

Even by the standards of Brazil, the last two decades of boom to bust to boom have been anything but unusual.

The third largest democracy in the world, the fifth largest nation by size, and the tenth largest economy is simply too large to be ignored.

Brazil, the seventh most populous nation, has everything that a nation needs to be a successful and wealthy and even a superpower.

The tropical nation is endowed with natural resources, mild weather, young population and away from a world of conflicts, yet the vast nation has struggled to rise above internal divisions and make a mark on the world or even in the region.

With 215 million people, Brazil has one of the most unequal societies in the world, one of the largest exporters of food has 33 million suffering from hunger and many lack access to higher education and clean and healthy living.

With less than 3% of the world’s population, Brazil feeds more than one billion people around the world.

For decades, what happened in Brazil rarely mattered beyond its borders and immediate neighbors, but the commodity super cycle of the last two decades thrust this backwater economy of happy and warm people onto the world stage.

Wealth Distribution Empowered Poor and Angered Middle Class

In a span of nine years, Brazil’s economy jumped five-fold between 2002 and 2010 and the once ignored nation was widely perceived as one of the fastest emerging economies with a serious economic potential rivaling the wealthiest of the nations.

The discovery of large offshore oil fields and China’s growing appetite for food came together to power the economic boom that most Brazilians could not even dream of.

This year-after-year economic advance lasting nearly a decade not only raised living standards of the middle class but also lifted millions from abject poverty because of the direct cash programs.

Small middle-class began to grow and solidify in this rapidly growing economy that became accustomed to stable jobs with escalating wages, urban living and rising aspirations. Population that had only seen inflation and hyperinflation in previous decades came to believe in the promise of rising Brazil where upward mobility was possible even for the poor.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva rode this commodity super cycle and saw his popularity swell to heights envied by most politicians around the globe.

Lula, as the former president is widely known, rose from living in slums in a room with a family of eleven, to lead the Workers’ Party and then the nation for two four-year terms between 2003 and 2010.

Brazil’s politics was undergoing dramatic and fast-paced changes and people who were occasionally visible in statistics were now controlling the levers of power.

Lula and his supporters implemented policies, which came later to be known as Bolsa Familia, that directed some of the new-found wealth in commodities to those in extreme poverty.

The small monthly transfers of less than $100, reached 4 million people and gradually expanded to 10 million covering elderly and handicapped, putting much needed cash in the hands of the poor who struggled for decades to make ends meet.

To the extreme poor, it was not the amount that mattered but the certainty of the transfer, month-after-month, provided the support to the segment of the society largely ignored by every government before.

Now these poor people had a direct tap in the fast-growing Brazil’s economy.

Other government programs supporting education and subsidies to the poor helped millions of families to keep children in school and acquire skills needed for the job market and break the vicious cycle of poverty.

Lula went from just another party leader, to an admired president, to a mythical figure that changed the livers of millions. The redistribution program that cost less than 0.6% of Brazil’s gross domestic product managed to change the lives of many, something that no government before managed to do.

President Lula was able to accomplish that because much of the rise in crude oil and iron ore exports were either in direct control of the government or controlled by the long hand of the government and with the support of the minority party in coalition bought through corrupt means.

However, those in the urban areas struggling to make ends meet, not too poor to benefit from the government programs and barely making, resented these direct cash programs to the poor.

To working poor families, these programs seemed nothing but a gigantic waste to keep the poor forever poor with a culture of dependency.

Oil Bust Realtered Brazil’s Politics

The good times came to a screeching halt with the collapse of international oil prices from $85 to $25 a barrel in less than a year beginning in late 2014.

The sudden and swift change in terms of trade left the subsequent government of President Dilma Rousseff in a terrible situation leading to her impeachment for the violation of budgetary laws in 2016.

President Lula was also convicted and jailed in April 2018 for 580 days but managed to overturn his conviction on technical grounds.

Politicians of all stripes have been deeply enmeshed in the construction-industrial complex of Brazil, with allegations of bribery and political favors always in the headlines at the time of presidential and congressional elections.

Operation Car Wash

For decades, Brazil has endured systemic corruption that financed expensive elections at all levels of government in this vast nation with multiple parties and deep divisions. People have been fed up with the endemic corruption and felt powerless after rarely witnessing a politician, wealthy businessman or a drug lord prosecuted.

Expectations were high and Lula’s Workers’ Party was elected on the promise of cleaning up corruption, but all that changed with the Operation Car Wash.

A routing corruption inquiry in 2016 turned quickly into a much bigger investigation and ended up uncovering an intricate web of money laundering, corporate racketeering and engulfed corporate executives, international companies and hundreds of politicians and lawmakers.

Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato) not only put many governors and politicians behind bars, impeached the sitting president Rousseff and locked up former president Lula but also pushed out the Workers’ Party from office in disgrace.

The investigation was not only successful in cleaning up corruption but for the first-time people felt that justice was served at all levels of the society after 13 years of power held by the left-leaning Workers” Party.

It did not help that the interim president Michel Temer, constitutional lawyer, was accused of multiple graft allegations, Temer’s administration had an approval rating of less than 10% and despite the widespread protests, Temer held onto his office two more years to 2018.

The collapse of the oil and iron ore prices and the disgraced exit of the Workers’ Party in 2016 came to a head with the ever-growing influence of evangelicals at the next presidential election in 2018.

Evangelicals Brought Religion to Politics

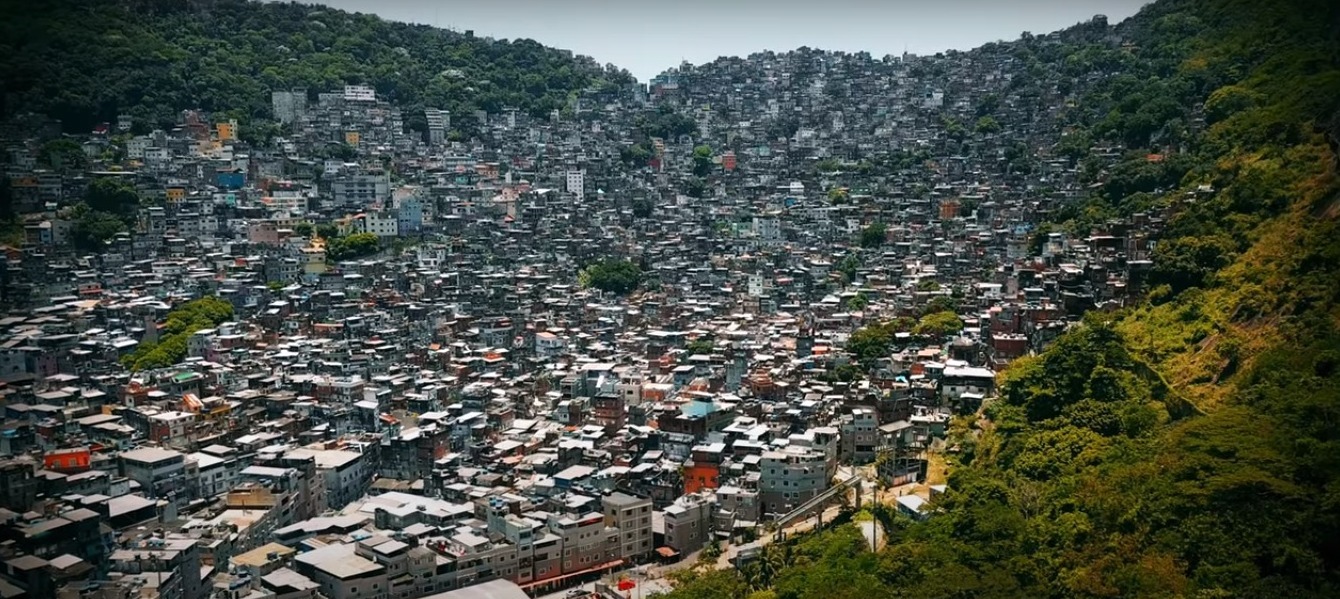

Commodity powered economic boom also accelerated migration of many from farms in search for better jobs in cities. These new workers on construction sites, factories or providing services to urbanites were untethered from their families and most endured primitive living conditions in favelas or blighted neighborhoods.

Though raised in Catholic traditions, these new migrants were left to fend for themselves in a heartless and competitive setting bereft of safety net. With ever present violence, drugs and little protection from the government or society, many needed emotional and financial support and above all how to navigate the local government.

Well-organized and well-financed volunteers of evangelical Christians filled the gap where Catholic church rarely provided more than lip service.

Whether it came to needing daycare for children, finding a lawyer to fight drug charges, negotiating with the police or acquiring a water and electric connection, the evangelical army of volunteers was always there to lend a helping hand.

This day-to-day hand holding in cities with no safety nets for the poor from the evangelicals has successfully managed to convert many migrants to born again Christians.

With the fading of the oil boom, Brazil entered into its deepest recession in 2015-16 since the record keeping began in 1901 and the economy shrank 7% in two years.

Oil Boom Turns to Agri Boom

But another boom was fast developing in agriculture commodities but visible only in the farmlands controlled by few farmers and away from major cities.

Farmers were becoming rich by exporting growing amounts of soybeans, sugar, meat and other agricultural products to China. The Chinese demand for these products is so strong that farmers in the U.S., Brazil and Argentina barely keep up. But Brazilian farmers dominated the international markets with vast fields, cheap labor and productive systems in place.

Despite the coronavirus pandemic, Brazil’s goods export engine is humming strong and generated $61.2 billion in trade surplus in 2021 and international trade of $500 billion accounted for 40% of its gross domestic product.

So, what happens in international markets has a lot of bearing on Brazil’s economy and its politics.

Soyabean, corn and sugarcane farmers, spread all around Brazil and staunch evangelicals, were getting rich by the bushel and by the day. Farmers for the first time began to express their religious views in elections and with the rapidly growing their evangelical faith even in the urban areas became a political force that no political party could ignore.

In other words, Brazilian farmers had finally arrived on the global scene and in the capital city of Brasilia for the first time ever.

While the oil and metals boom helped in eradicating extreme poverty, the agriculture commodities boom accelerated the spread of evangelical faith, in a majority Catholic country.

Brazil is the world’s largest Catholic country with more than 51% of its population following the faith, but evangelical churches are growing rapidly and now claim about one-third of the nation as its followers and about 20% of lawmakers in the Congress.

When it comes to opposing abortion, fighting violent criminals with gun culture, rejecting gay and liberal values, and actively participating in local and regional politics, evangelicals speak with more coherent voice.

Bolsonaro Taps Populus Anger

Jair Bolsonaro, former army captain and an admirer of military dictators, once the fringe candidate with extreme rhetoric had been in Congress for more than two decades before he began to emerge on the national scene.

Bolsonaro’s angry persona and right-wing views began to resonate with urban voters fed up with persistent violence, rural voters holding Biblical views, business owners yearning for corruption-free government, and middle class seeking a larger share of the commodity boom.

Bolsonaro successfully tapped into this rapidly evolving virtual coalition of mass support in a country reeling with crime, corruption and scandals.

This new Brazil wanted to fight crime with violence, liberate businesses from the government, shift government spending from the poor to the middle class and hold politicians accountable for their actions.

Elections in Brazil were often fought on personalities, support for the poor, fighting corruption and the very rich but never on religion.

With the emergence of Bolsonaro and evangelicals, God began to dominate the 2018 presidential race and continues to do so even today. It seems like God has finally arrived in Brazil and is checked in every ballot box.

“Brazil above everything, God above everyone,” the slogan that Bolsonaro utters at every political gathering, became a rallying cry among evangelicals.

Bolsonaro, a Catholic married to an evangelical woman, identifies closely with evangelicals in politics. His pro-gun views, misogynist remarks but above all his angry man rhetoric with insulting rebuttal and aggressive demeanors have found a solid footing among many disenfranchised by the politics of the left.

Change was in the air after the previous four presidential elections over 16 years favoring left-leaning candidates, and Bolsonaro was there to capitalize.

Bolsonaro won with 55.1% of votes, comfortably ahead of 44.8% of votes garnered by his rival Fernando Haddad from the Workers’ Party.

From Amazonas in the west to Espirito Santo in the east and Mato Grosso in the center to Rio Grande do Sul in the south, voters preferred Bolsonaro by a large margin in 15 of the 26 states.

Former president Lula tapped in the riches of the oil boom during his 2010 reelection, Bolsonaro tapped in the rapid-rise of evangelicals powered by the current soybean boom and anger against crime and corruption.

Bolsonaro with his fiery rhetoric and aggressive talk lifted hopes that the economy may take a different turn and improve the business climate for small and medium businesses. Bolsonaro never articulated his economic plans or set targets for economic reforms or achievements either.

For two years, coronavirus dominated the Bolsonaro administration’s term in office, with deadly consequences taking the lives of 680,000 people. The business-friendly administration struggled to implement a small economic agenda under the shifting policies during the coronavirus pandemic.

Bolsonaro also lost support of many inside Brazil and around the world after his relaxed policies accelerated the clearing of Amazon jungles setting the nation up for future climate disasters.

Road Ahead for President Lula

Lula returned to power for the third time with a thin majority after Sunday’s election in a country polarized along two axes of religion and societal hierarchy - Catholics vs Evangelicals and poor vs middle class.

The next president will have to win continual support on these two axes and programs and policies have to please these two groups.

President Lula has promised to link minimum wage with the inflation index, wages have been stagnant for four years in a country with annual inflation above 13%, and plans to expand direct cash benefits to the poor.

Middle class may see more riches from the current elevated oil price flow to the poor and bypass them again for the second time, and strong Chinese demand will empower evangelicals even more.

Brazil’s businesses will have to tackle a growing web of regulations and rising wages and can only hope that the vast spending of government contracts will become more transparent and accessible.

Brazil may see as many as 30 parties represented in the next Congress, making the next president’s job harder.

Bolsonaro may have lost the presidential election, but in opposition his party holds enough power to derail government plans. The Bolsonaro-controlled Liberal Party won 99 of 513 seats in the lower chamber of deputies, up from 77 in the last election.

Moreover, right-leaning parties now dominate the Congress and have increased their share in the Senate and made advances in state politics.

President-elect Lula has a fight on his hands, unlike in the previous two terms.

Despite the current boom in energy and agriculture commodities, Brazil’s economy is still smaller than it was in 2007 and since then the population has grown by 15 million from 190 million.

In the last fifteen years the basket of exported goods has dramatically changed, with more share of foreign earnings going to large farmers who are not likely to ease from their support of spreading the gospel of evangelicals.

Voters don’t think in terms of GDP and inequality but understand a paycheck and inflation, and on those two key measures, the next president has much taller hurdles to overcome.

And what about that talk of Brazil - the superpower in the making, well, that will require an election and candidates that put the economic growth, competitiveness, developing skilled labor force on top of the agenda.

Brazil’s productivity anemia and bloated public sector, built on one of the most complex tax regimes, needs much more than a leader who returns to office on the platform of corruption, crime and God.

Sustainable Middle Class Needs Sustainable Policies

Commodities boom and busts will come and go, but unless Brazil finds a way out of these cycles, this underperforming economy will remain trapped in the middle income with many surviving near the poverty line.

Much lauded and needed programs like Bolsa Familia, help in fighting extreme poverty but political leaders must acknowledge that the commodity booms create more unskilled than skilled jobs needed to build a stable middle class.

To create and expand the middle class, the hallmark of any successful society, Brazil needs a reserve fund that swells in the good times and available in the bad times, but ensures a stable economic growth that allows more people to acquire education and skills and creates a diversified economy.

Only about 25 years ago, Brazil was the sixth largest economy in the world and dynamic China, India and South Korea have surpassed Brazil by developing a sustainable middle class.

It is time Brazil moves beyond God, corruption and crime and develops a skilled labor force and embraces politics of meritocracy.